This article was originally published June 24, 2019.

On January 11, 1970, the NCAA broke the Busted Flush.

The Florida State men’s basketball program was banned from the 1970 and 1971 postseasons and one of the program’s best-ever teams would be denied a shot at the national championship.

The NCAA cited the Seminoles for recruiting violations while the team was already on probation from different transgressions in 1968, and the school placed restrictions on head coach Hugh Durham, removing him from all recruiting work, though he remained in his position.

“I read the NCAA manual carefully, and my decision to allow our basketball signees to talk with Atlanta businessmen about summer jobs was a rational one,” Durham said in a special news conference days after the NCAA’s ruling. “I could see no conflict, but the NCAA had a different interpretation.”

Florida State was 10-2 and undefeated at home, its only losses away from home against nationally-ranked North Carolina and USC. The Seminoles saw themselves as legitimate contenders to knock John Wooden’s UCLA Bruins off the three-peat throne. That disappeared with one meeting in an Arizona hotel during a road stretch.

But that would only be part of what made the 1969-70 Seminoles special.

—

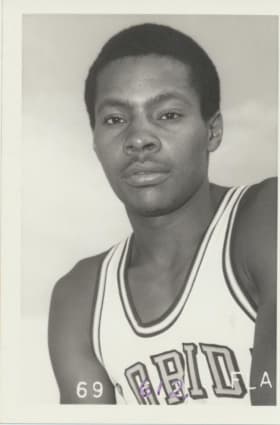

Skip Young grew up in Columbus, Ohio, and played his high school ball at Linden-McKinley High School. He gained attention for his play and entertained attention from some major programs, namely his hometown’s own Ohio State. His family and friends largely pushed for him to choose the Buckeyes, but he went against the grain and selected Florida State instead.

“The weather,” Young laughed. “But the main reason was the style of play. At Florida State, we were going to play a pro style, up-and-down type of style, which suited my particular style of play, and with a concentration on defense. Then the other was the competition. We had some great athletes. That made it kind of easy, because you knew you were going to play with some top-notch players.”

Before heading to Tallahassee, the Midwesterner had never been to the South. He was excited to make a name for himself in a new place. Young did not comprehend what he was walking into.

“To be honest with you, I basically didn’t give it a thought, which I should have,” Young explained. “I never really knew anything about the South, the history of the South. I didn’t know anything about Jim Crow, I didn’t know anything about historically black colleges. My only concern was to go to college.”

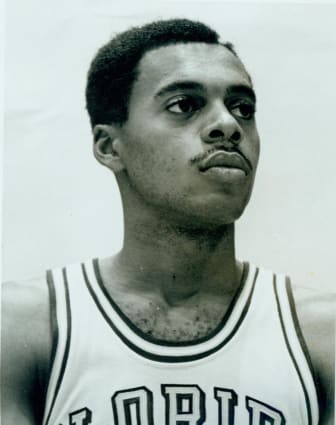

Kenny Macklin had a different path. He started in East Orange, New Jersey, but was the third-leading scorer on his high school team and didn’t get the recruiting attention he wanted. Macklin went to Morristown Junior College, a black school in Morristown, Tennessee. In his second season there, he averaged 30 points per game, and it brought his profile up.

He chose Florida State to finish his undergrad and slid south from Tennessee to Tallahassee. Unlike in Young’s case, Macklin had southern connections. His parents hailed from there, and many of his high school classmates attended historically black colleges below the Mason-Dixon Line, a handful at Florida A&M, a stone’s throw away from FSU’s campus.

That didn’t mean he was ready for it.

“I’m a kid. What kind of insight do I have as to how this Southern culture is going to directly affect me on a long-term basis?” Macklin recounted. “My family was in the South and some of my first experiences with being told I couldn’t eat at a particular lunch counter occurred in Virginia when I was 8 years old, but I was just down there for two weeks, and I was 8 years old. But this long term, day in and day out of feeling of being a fry in a bowl of milk was something different.”

Both Young and Macklin experienced rude awakenings when they arrived at Florida State. At first, they tried to behave as normal students, but that delusion was torn down efficiently.

“It wasn’t a warm welcome,” Young explained. “Almost like the first week I got there, I received several threatening letters, making derogatory statements and threatening me bodily harm.”

They turned to Florida A&M for their needs outside of hoops and studies. That’s where they made friends, dated and partied, living the standard student life on another campus.

“Remember what a fly in a bowl of milk represents: you don’t want that fly in your milk. Not only are you sticking out, you’re not wanted there,” Macklin said. “It was a matter of getting in where you fit in, and that’s where Florida A&M came in.”

But even being around Southern black people could be an issue.

“Some of the folks down there to this day still think the Civil War is going on. That’s both black and white,” said Macklin, a self-proclaimed city kid. “There is a disconnection even amongst black people if you’re viewed as some northern city slicker. Even amongst black folks at times, especially with other black men, there was always some kind of disconnect, some kind of tension, some kind of competition. It wasn’t a welcoming attitude.”

At Florida State, that feeling was tenfold, Macklin said. Young and Macklin, along with their other black teammates, had to deal with the stigma of big, black basketball players integrating into a white school. They received stares when walking the halls and weren’t taken seriously once they reached the classroom. And it didn’t stop with fellow students.

“I had a professor call me a derogatory name. He told me he would never allow anyone like me to pass his course,” Young said. “I told him he better never, ever call me that again or refer to me as that again, and I told him I was going to pass his course.

There was a certain stereotype of me being who I was, and on top of that being an athlete, so I must not have any intelligence whatsoever and the only reason I’m there is to play basketball.”

With help from an advisor, Young navigated the class and passed. But the attitude prevailed, and it wore on him. Young was so battered, he strongly considered transferring, even visiting other schools during winter and summer breaks his freshman year.

“We played Florida, and my roommate, I think he had 35 points, 25 rebounds, and I had 25 points, 19 rebounds and a bunch of assists,” Young remembered from his freshman campaign. “The Florida coach called the game the last seconds of the game, ran out on the floor and said, ‘We need to rid of these you-know-what, then we could probably win.’ Then we went down to Florida (later in the season), and we must have fouled out before we got off the bus. There wasn’t nobody black in the gym but us and the custodians. Those type of realities hit you.”

When Young went back to Ohio for the summer, he didn’t even want to talk to Tallahassee. Florida State would call his house, and he would not take the phone from his mother. She eventually told them she would talk to her son, and she talked him off the ledge.

“She didn’t like the coach and didn’t like the situation, but because that’s what I chose to do, she encouraged me to stick it out,” he said.

And stick it out, they did.

—

The 1969-70 Florida State Seminoles had black players, but it was not an all-black team. Its best player wasn’t even black: 6-foot-9 center Dave “Big Red” Cowens from Newport, Kentucky, averaged a team-high 17.8 points and 17.2 rebounds per contest.

The black and white players shared a locker room, but outside of the gym, they lived opposite lives. The black players used Florida A&M as their home base, while the white players could enjoy the fruits of being a student athlete at a major university on their own doorstep. The white players had the resources to afford cars, which meant more mobility and freedom. The daily stress as an unwanted outsider wasn’t there.

And the influx of black players meant some white players were losing playing time and roster spots, an easy cause for tension in any setting. It’s something Macklin understood from the beginning.

“You have to remember, we were taking their spots, so they had to make some adjustments with that,” Macklin said. “I’m not trying to toot my own horn here, but I know that some of my attitudes in some of my actions and things helped bridge that gap. I know that (some of my black teammates), at one point in time, they didn’t want to talk to nobody. I showed that, this is silly. That’s silly.”

The team would get taped up in the locker room before every practice, and Macklin used the captive audience to his advantage.

“I had a joke a day for a really long time until I ran out of jokes, and these jokes, they were long stories,” he explained. “They were these long stories that had no ending that would wind up being not funny, or part two tomorrow, those kinds of stories. Most of them were just made up stuff as I was going along when I had the attention of everybody, including the coaches. I thought that helped ease some tension, break some ice.”

Macklin and Cowens grew close, and one summer, Macklin hosted Cowens, Young and black teammate John Burt at his family’s home in New Jersey.

“So here it is: I’m an inner-city kid, and I’ve got this big, 6-foot-9 red, white kid staying at my house and playing ball in the neighborhood park. That was another thing that brought us all together,” Macklin said. “I think part of that was when the white players saw Cowens was connected with me off the court. This was not necessarily a basketball thing; we had developed a friendship. It was a process of blending together.”

Back in Jersey, there were hand signal Macklin said people in his neighborhood would sometimes use. Not gang signs, but symbols that communicated something to others. He decided to bring one with him to Florida State.

“I remember the very first game of the whole season, when they introduced me, I ran out onto the court with that hand signal over my head,” Macklin said, remembering putting his cupped hands above his head, forming two semi-circles, but keeping his hands separate to not complete the circle. “That picked up, Skip went out, he did the same. And then, all the rest of the guys, they followed suit. Durham was probably nervous, but when Red got introduced and did the same thing, that brought the crowd to a roar. That had I think everyone embracing, because Red was the white guy. He was the really good white guy. I think it unified us as a team and had the fans embrace us.”

Neither Macklin nor Young would reveal what it originally signified, both chuckling at the thought, although its meaning completely changed in Florida. But they did drop some hints.

“What it originally meant was something a little bit illegal, and I’m going to leave you to decide that,” Macklin laughed. “It was the ‘60s, and free love and all that stuff was happening. I’ll leave your imagination to that.”

Regardless, fans constantly flashed the signal to the players on and off the court, and it became the rope that tied it all together for the 1969-70 Seminoles.

—

Neither Young nor Macklin were positive of where the Busted Flush nickname came from. Young said he heard it started in Sports Illustrated and caught on from there but couldn’t be sure, and Macklin could barely make the same guess. But when it first started, Macklin didn’t like it.

“The word busted implied something negative, something that’s not so good,” Macklin explained. “And now they tell me something about some kind of poker thing. I don’t know about that; I don’t play poker. But that was my initial take on it, that it was something negative with a negative connotation to it.”

Although Macklin isn’t familiar with the game, the term originates from poker. It refers to a hand holding four cards of the same suit and one of a different suit, a mirror image of the 1969-70 Seminoles starting lineup.

But no matter the suit, cards are cards, and Florida State played like it had a royal flush.

The Seminoles started the season unranked and without the national attention they would soon require. They opened the campaign with a one-point victory against Oregon State, 69-68, then beat up on Oregon in their second game, 100-84. Two games later, the Noles fell for the first time, 86-75, to No. 5 North Carolina in their fourth matchup.

Then the bashings began.

Florida State won its next six games by an average of 27 points, including an 88-63 beatdown of archrival Florida and a 10-point victory over No. 14 Louisville.

It wasn’t just that Florida State was winning. It was about how it won.

“We were rugged,” Macklin said. “Fast paced and rugged.”

The Seminoles would run their opposition to death, pushing the ball in transition and playing a stifling defense built on physicality. Durham employed a 1-2-1-1 press, with Cowens and his wingspan on top of the ball, that would torment challengers.

“We were very quick, very aggressive, and I would like to think we were very cerebral basketball players,” Young said. “Everybody knew everybody’s strengths very well and complemented those strengths, even the people who came off the bench. There wasn’t much of a drop off at all, if any at all.”

Florida State lost its second game of the season at No. 19 USC, 71-68, nearly taking the lead in the final minute, but an outlet pass gone wrong ended that idea. The team bounced back against Arizona, 87-78, a couple days later, completing its West Coast road stand. As the players returned to their hotel, they had in-state foe Miami on their minds as they had a date with the Hurricanes in Tallahassee in a few days.

But they’d be hit with a curveball first.

Everyone gathered in the team’s hotel in Arizona, and the news dropped to the players: the Seminoles would be banned from the 1970 and 1971 postseasons. Florida State’s dream of competing for a national championship was dead.

“When we heard the news, there was a lot of disappointment and frustration,” Macklin remembered. “I think for my part, I was in denial of it. It was like, ‘Wait, what do you mean? What do you mean we can’t do this?’ And once it set in, I know that I was mad. I was angry. I was hurt.”

Without explanations from superiors, Macklin said some players on the team began to wonder if it was on them.

“There was a feeling of disbelief, there was no question,” he said. “Like, how could this happen? Again, that was one of those things that people began to think was their fault. No one from the university – no coach, no athletic director – said, ‘Listen guys, this is not your fault, this is what we do.’”

It wouldn’t be until February 2019 when Florida State honored the 1969-70 team at a regular season game against Georgia Tech that the players would receive a formal apology from the university, but even though it came decades after the fact, it didn’t stop the players from still giving it everything they had back in 1970.

Florida State took its anger out on Miami, smashing its rival 104-63, the third of six times the team would crack 100 for a game that season without the aid of a three-point line. The Seminoles continued their streak from there, racking up 10 more wins in a row, including an 89-83 victory over No. 6 Jacksonville in the middle, one of the premier programs in the entire nation at the time and eventual national runners-up. For their efforts against the Dolphins, the Seminoles were finally rewarded with a spot in the AP Poll, which they’d maintain for the rest of the season.

A four-point loss in a rematch with Jacksonville would stop Florida State’s string of victories, and it would be the team’s final defeat as it took care of Georgia Tech, Stetson and Miami in comfortable fashion to close the campaign. The Seminoles finished 23-3 and No. 11 in the country, according to the AP.

It would have been easy to give up when the penalties were levied, but Florida State didn’t. Why?

“We weren’t built like that,” Young explained. “You got a highly competitive team and a talented team. You got guys who came from, whether it was high school or junior college, winning situations. And so, you’re wired to be a winner. We felt that if we showed people through our play, just maybe we could get the type of recognition we deserved. In some instances, we did, but not when you have that black mark on you. I would say we didn’t fold because we were competitors. We believed in ourselves.”

—

It has been nearly 50 years since the final whistle blew on the 1969-70 season, but members of the Busted Flush team still haven’t gotten the hand they were dealt. UCLA went on to win the 1970 national championship, the program’s fourth in row and sixth in seven years. The Bruins owned college basketball from the mid-1960s into the mid-1970s, but Florida State felt it had a shot at Wooden’s dynasty.

“I still think about that,” Macklin said. “We’d read the paper, and we’re looking at what these guys do and what they’ve done, and here we are. We’re in a great position, because nobody really knows who we are. We knew that we were that school from the South that would get that bid. We just felt that. We really knew that it would be something we would be experiencing, so we kept it on our radar.”

Young focused less attention on UCLA and more on a chance to compete for a title.

“Certainly, we think we could have competed with (UCLA),” Young said. “But not just UCLA, but the opportunity to play for the NCAA championship, period. If we had to go through UCLA, fine, or anybody else, it really didn’t matter, as far as I’m concerned.”

That game never happened, and UCLA won the title without handling the Busted Flush. Florida State played out its regular season and stayed in the shadows for two seasons as it was stripped of the chance at redemption in 1971, too.

That was only one angle of the hardships Young and Macklin faced in their Florida State career. The regular trials and tribulations of being a young person and a major college athlete were there, plus the intense tension caused by the racial climate. They and their other black teammates had to navigate the front lines of a social war while remaining focused and dedicated to their sport and team.

Being a black student at Florida State was not an easy task at the time. In fact, it was virtually impossible to the point that those students spent more time at Florida A&M than at their own school.

But when I met Young at a basketball event in Columbus, Ohio, a few months ago, he was decked out in garnet and gold. He had on a garnet FSU jacket with the logo and “23-3” inscribed under it, plus a Florida State ball cap for good measure. Despite the rocky time in Tallahassee, Young has great pride in his alma mater and proudly sports its colors wherever he is.

“I think the overall experience of going to Florida State makes me a better man and a better human being,” Young explained. “It gave me strength to be able to face adversity and feel I can win regardless of setbacks, regardless of being labeled by people.”

He said that being put in the situations he was forced him to open his world up to people unlike him, a valuable lesson for any young person.

“The experience, the social experience, was enlightening for me, more so than the basketball, because I had to learn about other people,” Young said. “I had to learn more about my own people and myself. I had to learn how to control my anger and hostilities and make my adjustments to get through, socially and even academically.”

Macklin shared a similar sentiment. For as much bad as there was during his time at Florida State, there was plenty of good, and he loves the school that awarded him a diploma.

“I could be a curmudgeon about that whole thing and look at the negative aspects of my experiences there, but that’s no good for me,” he said. “That’s not a warm fuzzy. I like to live in warm fuzzyville. Call me naïve, but this is where I live, and I like to be able to identify, think about and talk about that total experience, and part of my total experience was some good stuff.”

When Macklin joined the rest of his former teammates in Tallahassee for the reunion earlier this year, an equipment manager tapped Macklin on the shoulder and asked him to follow him. He took him to the equipment room stocked with sneakers, jerseys, helmets and all things Florida State, then handed him a bag full of stuff, a reminder to Macklin that he is now appreciated by his school.

“That’s the way you get treated when you get back there,” he said. “I got nothing but love for them now. There’s no sense in me having anything else, you know?”

—

All these years later, members of the 1969-70 Florida State team are still close. When they reunited in Tallahassee in February, it was as if they never left the locker room, listening to Macklin yammer on about a fictional flop of a story. Individuals have maintained their own close relationships with one another, and the situation with the university has been largely rectified.

The stink of probation still sticks with them, though, and it’s a void that won’t ever be repaired. We will never know for certain if the Seminoles could have put a dent in the sport’s greatest dynasty, an unfortunate fact of the last 50 years.

But the Busted Flush doesn’t need a national championship to make a statement. Five decades removed from commanding the court, and they still hold that attitude with them.

“You better find out who we are before we pull up on you and pull your door down,” Macklin said. “You know, I guess it’s like some bad boys who didn’t get invited to the party, show up to the party and start taking all the girls.”